Climate Change and Green Infrastructure in Duluth, Minnesota

A Connection to Water

Duluth’s storied history is one intertwined and connected to the region’s beautiful natural waters. The traditional Indigenous inhabitants of this land, the Ojibwe Band of Anishinaabe, named our Great Lake Gichi-Gami and relied upon its vast clear water for both food and transportation. In the mid-to-late 1800s Duluth served as a vital commerce hub for the blossoming lumber and mining industries. Situated as a port city at the mouth of Lake Superior, natural resources extracted in Minnesota’s North Shore and Iron Range regions were exported from Duluth and transported eastward across the freshwater seas. By 1870, Duluth was the fastest growing city in the United States, with a population expected to surpass Chicago, Illinois in only a few years’ time.

While the rapid growth of the 19th and 20th centuries has slowed, Duluth’s many characteristic water features continue to provide an essential resource for local residents and tourists alike. With 129 parks and 11,000 acres of green space that prominently feature 60 named streams and rivers, the City of Duluth offers impeccable access to some of our state’s most beautiful natural surroundings and pristine aquatic ecosystems. These natural features substantially contribute to Duluth’s tourism industry, attracting an estimated 6.7 million tourists annually. Taken collectively, the City of Duluth is uniquely defined by its relationship to water, and the unparalleled beauty of its natural spaces.

Duluth and the Changing Climate

Future projected changes in Duluth’s climate pose serious risks to the City’s communities and natural ecosystems. The climate of the Midwest Region of the United States (and Duluth) is predicted to become warmer and wetter, with more frequent intense precipitation events. While the projected effects of climate change are well understood, in many ways, the climate of Duluth is already changing. From 1950 to 2015, Duluth experienced an increase of 1.8°F in the average annual temperature, an increase of 11.1% in annual precipitation, and a 37% increase in the number of heavy precipitation events. One such precipitation event in 2012 resulted in over 10 inches of rainfall in only a 24-hour period, ending in widespread community damage and a FEMA Disaster Declaration.

A 2017 report revealed that Duluth’s winters are among the fastest warming in the United States, with the average daily temperature for December, January and February now 5.8 degrees higher than in 1970. Duluth is also seeing more snowfall, going from an annual average of 86.1 inches in 2010 to 90.3 inches now. Recent estimates show that the climate of Duluth is changing at a rate equal to moving the entirety of the City 145 feet in the southerly direction every day, and, that by the year 2040, summertime conditions in Duluth are anticipated to be similar to those today in Rochester, Minnesota, Saginaw, Michigan, and Worcester, Massachusetts.

The Need for Resilient Stormwater Infrastructure

Dealing with the projected (and already experienced) changes in Duluth’s precipitation will require robust stormwater management systems. To ready our City for the threats of climate change and avoid potentially disastrous flooding situations like those of 2012, it is crucial that we ensure the proper mechanisms are in place to quickly and efficiently store, slow down, or transport stormwater away from areas that may damage human life and property. To protect our many beautiful flowing waters and Lake Superior, we must also ensure that pollutants from our City are properly managed, and are not carried into bodies of water by stormwater flows.

Much of Duluth’s existing stormwater infrastructure is very old. Many of the stormwater sewers, culverts and tunneled creeks (known as gray infrastructure) that Duluth relies upon to remove water after rain events were built in the 1800s, and approximately 36 miles of these structures are over 100 years old. Because it is so expensive to replace these structures, it is often difficult for the City to secure the funding and staff capacity necessary to make these improvements happen. While green infrastructure (more on this in a bit) represents a novel opportunity to improve both the climate resiliency and water quality of Duluth, reliable and functioning gray infrastructure will remain a crucial tool to our City’s ability to withstand the uncertainties of climate change.

What is Green Infrastructure?

Green infrastructure refers to infrastructure that has the ability to store or slow down stormwater, usually through the usage of plantings or foliage. Green infrastructure can take many different forms in Minnesota; a few examples include:

- Rain Gardens

- Tree Boxes

- Green Roofs

- Habitat Restoration/Pollinator Habitat

The usage of green infrastructure, while useful for improving water quality and reducing flood risk, has the potential to confer other benefits to the City of Duluth. Often referred to as “stacked benefits”, the additional features of green infrastructure include habitat for wildlife, increased urban shading, and the creation of more beautiful scenery to enjoy. When used to support Duluth’s existing gray infrastructure, green infrastructure will serve to improve water quality and reduce flood risk, all while making our City more sustainable in other ways.

On April 12th, 2021, Duluth City Council declared climate change an emergency and called to improve stormwater management, especially through the use of green infrastructure. Keep reading to find out how the City of Duluth will make this happen.

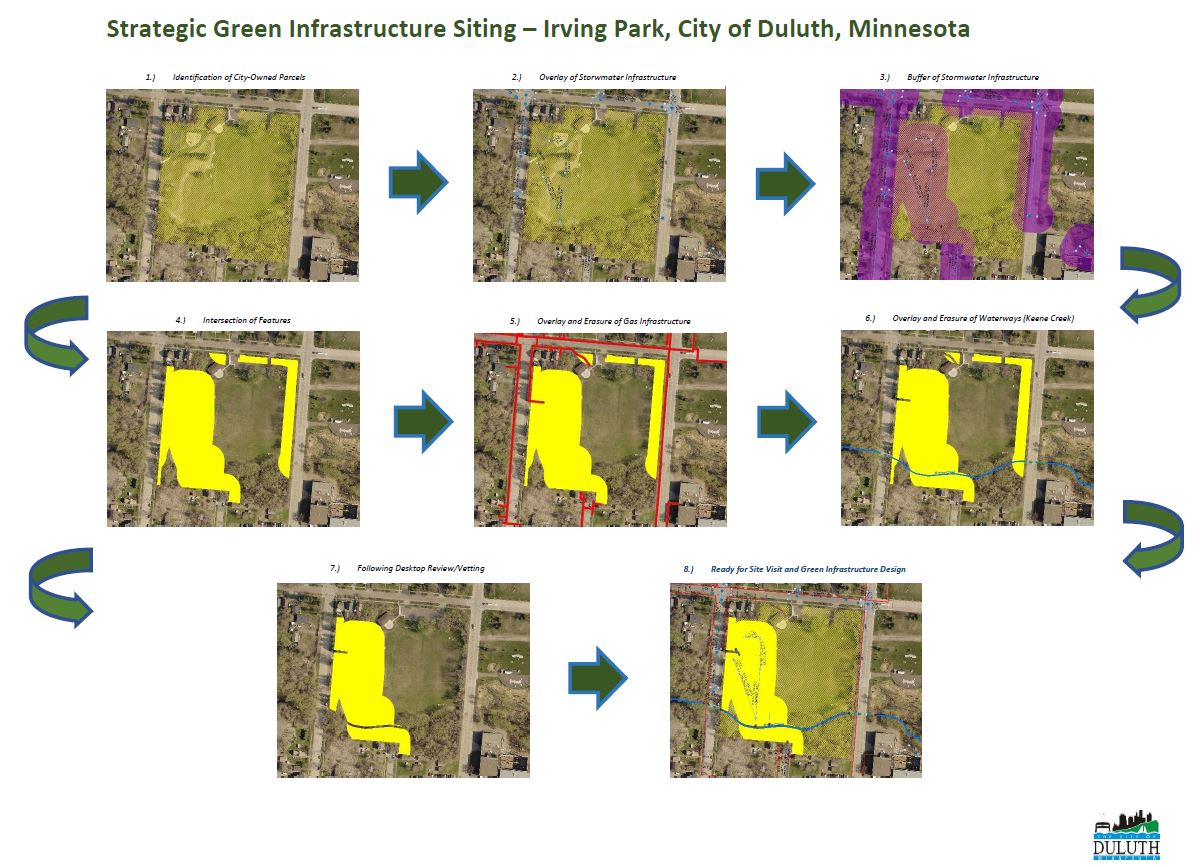

Strategic Green Infrastructure Siting

In September of 2021, the City of Duluth began to research where in our community green infrastructure would be most effective at improving water quality and increasing community resilience. Modeled after a similar mapping effort developed by the University of Minnesota Institute on the Environment, Duluth stormwater engineers, utility program coordinators and sustainability professionals utilized a geospatial approach to identify over 17-million square feet of potential sites to install green infrastructure. The project prioritizes City-owned land where stormwater infrastructure is already present (i.e storm drains or culverts). After removing features that prevent the development of green infrastructure (like flowing streams or existing gas utility lines), remaining areas were assessed to see how well they would utilize green infrastructure. An illustration of this process in the area of Duluth’s Irving Park can be found below.

This mapping project will allow the City of Duluth to envision specific green and gray infrastructure improvement projects intended to enhance community stormwater resilience, improve the quality of our essential water features, and bring about the multiple benefits listed previously. This effort will strengthen our City’s position to receive federal infrastructure funding, and provide an avenue for creating a more climate-ready Duluth.